>> learn // professional development experiences // mister lee konitz

I

A few months ago, my good friend Dr Jared Burrows told me that he would be on faculty with the 2007 Stanford Summer Jazz Workshop. It so happened that I would be in San Francisco during the week of the 'jazz residency' which is that part of the workshop where adult musicians, jazz pedagogues, and up-and-coming professionals could interact with such historical luminaries as Jimmy Cobb, Eddie Gomez, Kenny Barron, and Lee Konitz alongside younger player-educators such as Roni Ben-Hur, Julian Lage, Yosvanny Terry, and Victor Lin. As a jazz studies major, I was definitely quite familiar with the playing and recordings of the former three, but I'm afraid that I haven't checked out much of Mr Konitz's playing nor have I heard of any of the younger faculty.

Last year, I had the fortune of recording an album with Jared, Vancouver-based drummer Stan Taylor, and British saxophonist Len Aruliah. In preparation for that recording, we picked a bunch of tunes that each player had written and ran through them figuring out such details as the arrangements, tempos, and the order of soloists. As we were rehearsing the compositions, it became immediately apparent that Len's approach to improvising was indeed something special. He was playing with such facility and the note choices in his solos were logical developments of fresh melodic fragments. Part of the approach to improvising that I was taught in college was to learn licks and riffs from the printed page as well as from listening to the bebop canon. Len's playing seemed to come from a different angle altogether and I asked him about his approach. What I remember of that conversation was two things: he completed a degree in classical saxophone performance and he greatly admired the work of Kenny Wheeler for composition and Lee Konitz for improvisation. This was quite different than reading Bird licks from the Omnibook or lifting Sonny Rollins lines and playing them along to Aebersold recordings. [Something, I'm not afraid to confess, I still do from time to time!]

The other time I heard Mr Konitz's name was when my first college bass guitar teacher, Andre Lachance, announced to me in a lesson one day that he landed a gig with Mr Konitz along with Vancouver drummer John Nolan at a now-defunct Vancouver jazz bar called the Cotton Club. I didn't have the chance to attend that particular gig, so I asked Andre at my lesson the following week how the gig went. I remember two observations that he shared with me. At the gig, Andre asked,

"What would you like to play tonight?"

"Oh, you know … old chestnuts by white Jewish guys!"

Because the instrumentation on the gig consisted of alto saxophone, double bass, and drum set, there would be no chordal instrument providing background accompaniment figures. As a musician with perfect pitch Andre found that he had to continually adjust his bass notes to compensate for Mr Konitz's playing. It's true: Mr Konitz plays tonally sharp. In fact, at one point, according to Andre, Mr Konitz turned around on the bandstand and fiercely said to Andre, "Quit doing that!"

II

I arranged to get a one-day pass to the residency through Jared's best friend Rob Kohler, director of education at the workshop and a fine bass guitarist and great educator in his own right. The pass afforded me the opportunity to attend theory classes, instrument master classes, improvisation classes, the jam sessions, and the faculty concerts.

The first thing I checked out was Eddie Gomez's bass master class. After playing a tune with a faculty pianist as an introduction to the class, it was immediately clear why he was Bill Evans's bassist of choice from 1966 to 1977. He essentially took over where Scott LaFaro, the vanguard bassist who died in a tragic car accident, left off. The interactive and highly contrapuntal style of playing that LaFaro initially developed was extended and expanded by Gomez during those 11 years.

After a round of applause by those in attendance, Gomez invited the bassists to introduce themselves. Some played double bass while others played bass guitar. After everyone had been introduced, Gomez immediately affirmed the validity of both instruments in a straight-ahead jazz playing context.

Gomez said that it was important to understand the legacy of playing techniques that had been developed for the bass guitar and to allow those techniques to shine through. As an example, he encouraged the players to use chords being that the bass guitar was part of the guitar family. As a bass guitarist, that kind of affirmation spoke volumes to me especially since those words came from someone who played the double bass and who was a fixture in one of the most important groups in the development of straight-ahead jazz.

He then proceeded to play using the bow, in an achingly beautiful way, the melody of How Insensitive by Antonio Carlos Jobim. The sheer simplicity of that melody combined with his enormous musicality sent chills up my spine and nearly caused tears to roll down my cheeks. It was really that beautiful. Using the bow, as he reminded us, is part of the history of the double bass and is something that many jazz double bassists seem to forego or forget about. He surmised that by limiting our view of the history of either instrument, we also limit the possibilities that could exist to sonically contribute to the jazz vernacular. In extending Gomez's thoughts, I believe that we also potentially inhibit the possibility for exploring ideas which could effectively contribute to the development of our artistic voices.

III

I spent the early afternoon attending saxophonist and Berklee educator George Garzone's lecture on triadic chromatic improvisation. His concepts seem simple enough on paper, but incredibly difficult to properly achieve without focused practice and facility on one's instrument. These concepts were well executed and developed within the context of The Fringe, a Boston-based improvisational trio. The rules seemed simple enough: start with a root position major triad, move a half-step in either direction, then play another major triad in a different inversion.

It was at this lecture that I first heard Mr Konitz.

Throughout Garzone's lecture, a man kept heckling from the back of the room [where I sat] making snide comments and remarks about what Garzone was saying. Garzone was always respectful in his replies to the rude older man and it was clear that he didn't know that this man was Mr Konitz. [My good friend John Paton who was also attending the workshop alerted me to this fact after I quizzically asked who this older man thought he was.] In essence, Mr Konitz was questioning the ideas that Garzone was putting forward since the younger players in the audience might take those ideas too closely to heart without first developing a keen sense of improvising using the melody. Garzone's concepts on improvisation, to my ears anyways, made use of a lot of density and is an angle on the 'sheets of sound' concept that John Coltrane was going for. From the comments Mr Konitz was making, I was starting to get an idea of where he was coming from in terms of his approach to improvising. The end of the workshop culminated with Garzone's comment on students acquiring their own sound: "When you hear Lee Konitz, you know it's Lee Konitz." As John said to me afterwards, "Dramatic irony, at it's best!" Mr Konitz went up to Garzone afterwards and I didn't have a chance to introduce myself to let him know that I wanted to sit in on his afternoon combo class.

IV

John had been playing in Eddie Gomez's and Mr Konitz's combo master class back to back for the past three days and he was feeling quite overwhelmed with the information he was receiving. In particular, he surmised that there were some very specific improvising concepts and time feels that Mr Konitz wanted to get across but couldn't. John felt, however, that Mr Konitz was not able clearly articulate his ideas for the young players in his combo so that they could understand and execute them. Perhaps Mr Konitz was used to working with more experienced musicians who perform at such a high level that certain concepts are simply automatic while those newer to playing jazz need a little more time to ingrain these ideas. We also talked about Mr Konitz's rather salty character in the way that he was sarcastic and sometimes downright demeaning with the workshop participants in John's combo. After this conversation, I certainly had an impression of who he was in my mind. Still, to be able to sit in on a coaching session with someone who had been an influence on the direction of modern jazz would be an incredible treat. I had to be prepared for certain remarks to be flown my way, but what happened at that late afternoon gathering would be an event I wouldn't soon forget.

While waiting for the session to start, I sat patiently and quietly outside of the rehearsal room and along walked Mr Konitz. We made brief eye contact and nodded to acknowledge each other's presence. When it was time, I properly introduced myself and addressed him as Mr Konitz. I respectfully asked if I could sit in with the class. I was always taught to respect my elders as a youngster and while I had certain preconceptions of Mr Konitz, I was still cognizant of the fact that I was in the midst and presence of a master musician. Everyone has a story of how they came to be, and I wanted to find out his.

"What's your instrument?"

"I'm actually a choral conductor, but I was a jazz studies major on bass guitar and drum set. I won't be playing, I'll just listen."

"Ahhh. Okay."

I suppose that it was a bit of a ruse telling Mr Konitz that I was more of a choral conductor than a bassist or drummer. I suppose that the truth of the matter is that I am equally all three: a jack of all trades and a master of none. I just wanted to be a fly on the wall. Enough clichés.

In fact, clichés are what Mr Konitz abhors. From the interviews I had read and from conversations with John, Mr Konitz was a true believer in playing in the moment, like many jazz musicians. He'd rather that musicians not resort to licks and instead focus on the development of the melody as the primary vehicle for improvisation. He developed a graduated process where the first step is playing the melody exactly, note for note, and the final level is complete pure improvisation. Along the way, the melody is embellished and displaced and compositional devices such as elongation and diminution could be employed. By the end, the melody becomes abstracted to the point of becoming an entirely new theme. At least, that's what I think the process produces.

To some degree, a modified version of this concept is where I am at with developing my own voice on the instruments that I play. Mr Konitz had worked with two of my all time favourite bass players Charlie Haden and Steve Swallow. To my ears, their personalities are completely revealed through the way that they approach improvising. Neither barrel through their solos with stock trademark licks [though I would say that both players have tendencies]. Each note in their solos seems to be carefully considered, appropriately timed, and phrased impeccably. It was as if each note was placed right where it should have been.

I entered the small rehearsal room and I sat on a chair between Mr Konitz and the piano player on one side of the room. I proceeded to take out a pen and some paper to take notes. I wanted to gather as much insight as I could from this master musician. The rest of the small combo poured into the room and set up their instruments. The plan for the next hour and a half was to run through the song Ladybird, a tune based on the changes to All The Things You Are written by Mr Konitz entitled Thingin', and an open improvisation piece culminating in a section of 'time no changes' that would comprise their set for the following day's recital.

Mr Konitz counted off the first tune, and within the first few bars it was readily apparent that all of the student-musicians in this combo, including my friend John, were technically capable players for their age. In fact, I would say that when most of my peers were that age, the technical facility wasn't as keenly developed. Each student-musician had a chance to take a solo and though there were certain issues with pacing, phrasing, and keeping steady time they held their own rather respectably. I was also impressed with how well they could hear the chord changes.

I was, however, befuddled by the drummer. He had 'the look.' It was the same kind of look that befitted all hip players some twenty or thirty years his senior. The head nodded, the chin jutted out, and the eyes squinted and was nearly closed signifying to others watching that he was concentrating hard at what he was doing. I'm not sure that he was allowed to have 'the look' though. Perhaps he was working too hard maintaining 'the look' while letting the time feel slip around. It was clear to me: he filled needlessly and hit the 'and' of beat 4 too early each time. He clenched his sticks tightly as he played which caused the tone of the instrument to sound choked.

The band ended the tune. The drummer thought it was totally happening. I look to Mr Konitz, and Mr Konitz looks to me.

"What do you think of that, boss?"

"Truthfully?"

"Of course truthfully, no f***ing around, just get right to the point!"

So, I did. I said that the time feel of the whole group was inconsistent. I offered my two-bits and directed most of my comments directly to the drummer. He looked at me as if a big question mark appeared in a virtual thought cloud above his head. In hindsight, I was probably a little harsh in my delivery, but Mr Konitz told me to get straight to the point. So, I did.

The band tried the next tune and the drummer attempted to skeptically work with my suggestions. Subsequently, the time feel improved slightly. Interestingly, this was Mr Konitz's combo class, not Mr Trinidad's. Why would he ask me for my suggestion? I was just a choral conductor, who played some bass guitar and some drums, remember? Perhaps Mr Konitz was testing me. Maybe he wanted to make a fool of me. It's also possible that he genuinely wanted my opinion. Either way, I was happy to participate in the process of helping these student-musicians.

Lastly, the band attempted the open improvisation. Mr Konitz coached them through the order. Each player, starting with Mr Konitz, would take an open solo and the next student-musician would attempt to continue that solo by taking the last few phrases and using that as starting material. The last soloist would be the drummer who would then setup the time whereby the rest of the players would join in playing freely. In reflecting with John afterwards, and though I very much enjoy listening to open improvisation, it seems that most times when playing freely there are parameters within which musicians will operate in order to have a starting point. It certainly is much more difficult to simply play from nothing. Even when playing from nothing, musicians will make certain choices internally: do we aim for form, do we aim for timbre, do we go for time, do we deal with dynamics, or do we wait patiently in silence looking for the most opportune moment to contribute?

The group valiantly attempted to play openly and freely, but it was clear that these student-musicians didn't have as much experience playing in this manner. Each solo sounded rather stilted and contrived as if each player didn't really know what to do. Now, I didn't know if Mr Konitz had been explaining any of these concepts with these student-musicians before today. With the intensity of the workshop, it is quite possible that everyone was just feeling burnt out with nothing more to say with their instruments.

Once again, Mr Konitz turns to me and asks me for my opinion. Maybe Mr Konitz was also feeling burnt out with nothing more to say. So, I said:

"Sorry guys, it's totally not happening. I don't get the sense that people are truly listening to each other. What are your intentions when you play? Do you mean every note? Or is it just something that comes through without any thought? Are you truly present in the moment? Are you creating something or recreating something?"

Then, I got on the drummer's case again. Something about his 'look' just bugged me, and for some reason, I felt the urge to 'tell it like it is' once more. At the point where the drummer started playing time, the groove wasn't settled. The drummer was playing in a busy fashion and was trying to be too hip. And, the funky face was still there. It occurred to me that Mr Konitz's system of graduated improvising based on the melody could be applied to drum set accompaniment. The recipe could be something like this: start with the most basic groove using a sparse number of instruments on the drum set, lock it in with the bass player, lightly begin interacting with the rest of the rhythm section, and start setting up different accompaniment ideas based on the melody of the tune. With each passing chorus, the idea would be to gradually build to some sort of climactic point all the while supporting the soloist. Simply put, take care of basic business first before getting hip.

This is a particular approach based on a certain way of playing as a rhythm section. Obviously, other models exist out there of different ways of interacting. I like to be able to access and study these different styles of playing especially since I play both bass guitar and drum set.

I glanced over at Mr Konitz and he was smiling at me. He was nodding in affirmation at what I was saying.

"You can call me Lee, you know."

"That's okay. I call you Mr Konitz because I respect who you are."

"Oh? … Thank you."

At this point, one of the student-musicians piped up and asked me who I was. And, I reiterated what I told Mr Konitz earlier: I'm a choral conductor who plays some bass guitar and drum set. I also told them that I was a friend of John's [their bass player], Jared, and Rob Kohler. I'm not sure if any of these things validated my presence in the room or gave me any additional credibility as my own intention was simply to listen to Mr Konitz and to absorb what he had to say. It seems, however, that perhaps my place here was to humbly use my gifts as a communicator and teacher to help articulate what Mr Konitz had been trying to get this group to do all week.

They tried the open improvisation piece again. Immediately, the atmosphere changed. Suddenly notes and sounds played by each student-musician seemed carefully considered. As phrases and melodies were passed from one player to the next, the positive feelings were displayed on everyone's faces.

Throughout the afternoon combo session, Mr Konitz was playing along. In fact, it was clear that he was able to better demonstrate his ideas through his playing rather than trying to verbalize his concepts. It was remarkable to hear how this man, at close to 80 years of age, was still trying to create something new and fresh. And, he was trying to do this by going back and revisiting that basic element of the melody and developing something from there. My hope is that the aspiring student-musicians in this combo can see what Mr Konitz was going for and that this legendary master musician truly embodies the spirit of jazz in the way that he plays.

The session ended with a few more run-throughs of the other tunes and the same sentiment pervaded those songs as well. Mr Konitz, John, and I remained as the student-musicians cleared the room. Mr Konitz took out a banana to eat and a short conversation about rhythm sections took place as Mr Konitz recounted sessions that he had with Dave Holland and Ed Blackwell where he felt that the groove was not totally happening. I suppose it goes to show that even the most revered musicians do not necessarily gel.

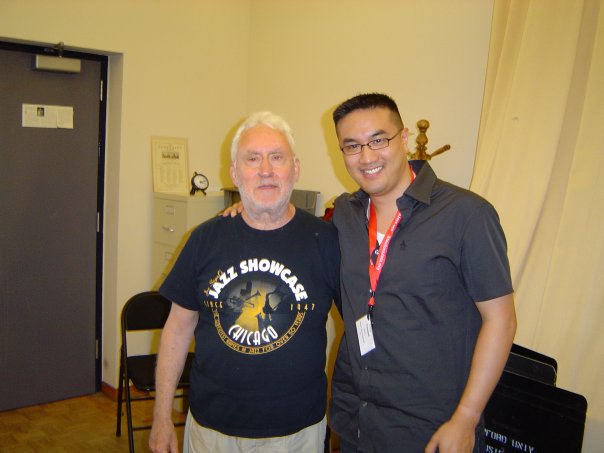

As John was packing up, I was thinking of questions to ask Mr Konitz. Here was my chance. Sadly, nothing came to mind. Maybe I was too absorbed in that moment to care to have any questions answered. I then asked Mr Konitz if it was alright for me to take a photo with him.

"Sure, if you don't mind me eating this banana."

"Uhm … no problem."

He actually put the banana aside and John took the shot. Mr Konitz and I posed to freeze that moment in light and in time.

V

My day at the Stanford Jazz Workshop was made complete with an evening performance featuring George Garzone on tenor saxophone, Eddie Gomez on double bass, Andrew Spleight on alto saxophone, Kenny Barron on piano, and Jimmy Cobb on drum set. Truth be told, I wasn't fully engaged in the concert at all as I was recollecting the day's experiences.

Hanging out with Mr Konitz made Len's playing and Andre's story much more life like for me. John's impressions about Mr Konitz were not totally unfounded based on my perceptions. Sure, Mr Konitz came from a different era and grew up in a different time.

After I got back to Vancouver, I scoured the Internet for any interviews or record reviews of Mr Konitz that I could find. Surprisingly, there was a lot of material available. I still wonder, however, why he wasn't regularly discussed in our college jazz history class and included biographically amongst the pantheon of other jazz legends. Was it because he represented a faction of musicians who were influenced by Lennie Tristano and not necessarily by Charlie Parker? Was it because he was always searching and refining his ideas that the jazz intelligentsia never fully caught up to him? Perhaps his playing, which is not flashy or adorned with licks and riffs, was not appealing enough to younger student-musicians.

Whatever the reason is, I now realize that I might never again have the opportunity to ask Mr Konitz the questions I wanted to ask. Questions like: Why did you develop the 10-step approach to melodic improvising? What was it like to apprentice with Lennie Tristano alongside Wayne Marsh? What was it like to play with Charlie Haden? Or Steve Swallow? Can you tell me a story about performing with Paul Motian?

Maybe having these questions answered doesn't really matter. Maybe it was about questioning answers rather than answering questions. Maybe, as Steve Martin so eloquently put it, "Talking about music is like dancing about architecture." Now, we have Mr Konitz's recorded legacy. And, he's still playing, he's still recording, and he's still searching.